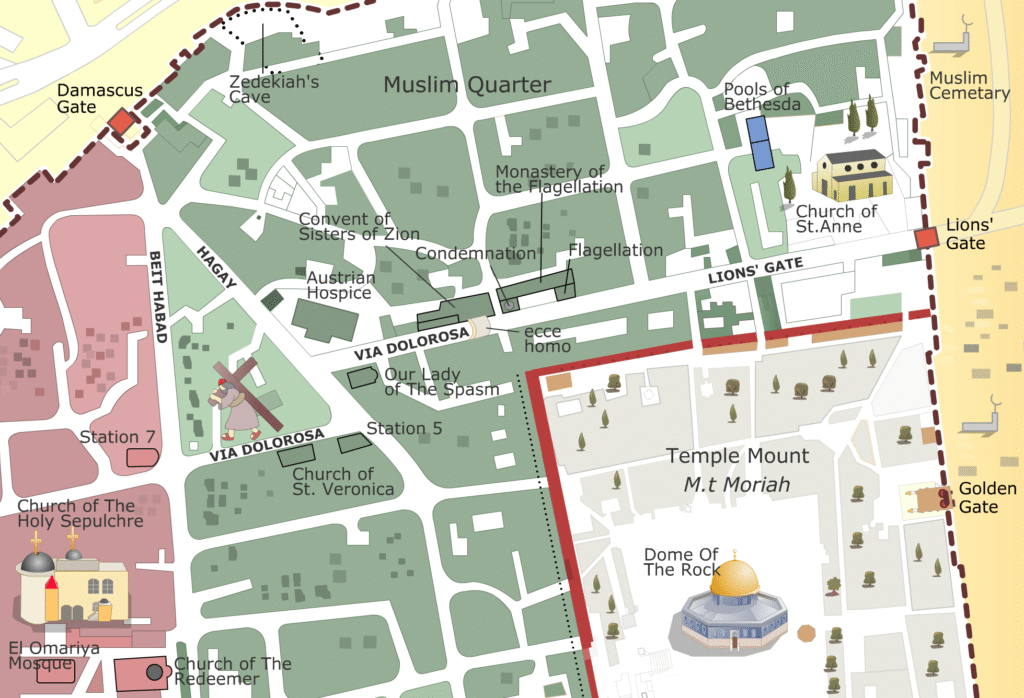

Muslim Quarter Map

This map of the Muslim Quarter highlights the Christian sites, structures from the Second Temple period, monasteries, and the route of the Via Dolorosa.

The Pools of Bethesda and St. Anne’s Church

Monastery of the Flagellation

The Convent of the Sisters of Zion

Via Dolorosa Station 7

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Ecce Homo Arch

is a prominent Roman-era arch that spans the Via Dolorosa. Its name means "Behold the man" in Latin—referring to John 19:5, where Pontius Pilate presents Jesus to the crowd before the crucifixion. While traditionally associated with this biblical moment, the arch itself likely dates to the time of Emperor Hadrian (2nd century CE) and was part of a Roman triumphal gate.

The Church of St. Veronica

The Church of St. Veronica on the Via Dolorosa marks the traditional site of Station 6, where Veronica is said to have wiped the face of Jesus. This story is not found in the Bible but comes from later Christian tradition, which also links her name to the phrase vera icon, meaning true image.

Site 1

The Pools of Bethesda and St. Anne’s Church

If you are planning to walk the Via Dolorosa, this should be your first stop before the First Station of the Cross. Whether you enter the Old City through Lion’s Gate, or finish the Western Wall Tunnels and step out nearby, you are already a few steps from a place you should not miss. If you can spare a little time, the Pools of Bethesda and St. Anne’s Church bring together a clear New Testament story, layers of Jerusalem’s history, and one of the most beautiful Crusader churches in the city.The entrance opens into a quiet garden and the complex also has restrooms, a small but helpful detail when touring Jerusalem.

The Pools of Bethesda – Healing and History

The Pools of Bethesda, the House of Mercy, appear in the Gospel of John. Here Jesus healed a man who had been paralyzed for thirty-eight years. The story is recorded in John 5:1–9. Archaeology reveals two large pools with five porticoes, matching the Gospel’s description. The oldest pool dates from the time of Herod the Great and originally collected rainwater. Over time, the site was expanded. During the Roman era the southern pool continued to function as a place for ritual bathing and for healing. On the site you can see remains of both pools, including ancient steps that once led down to the water.

St. Anne’s Church

Next to the pools stands St. Anne’s Church. It was built in the twelfth century by the Crusaders over the traditional birthplace of Anne, mother of Mary. According to tradition this was also the birthplace of the Virgin Mary. The church was completed around 1138. After the conquest of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187, it was converted into an Islamic theological school known as al-Madrasah as-Salahiyya. In the nineteenth century the Ottoman Sultan gave the site to France as a gesture of thanks for French support during the Crimean War. Since then custodianship has belonged to the White Fathers, a Roman Catholic missionary order officially known as the Missionaries of Africa, who continue to care for the church and the archaeological site.

Inside the church you can still sense the quiet beauty of its Romanesque architecture. Thick stone walls and high arches create a natural echo so even a single voice carries like a choir. Many visitor groups pause here to sing a hymn or simple song, relishing the acoustics. It is considered one of the finest surviving Crusader churches in the Holy Land.

The Deeper Meaning – From King David to Jesus

The healing at Bethesda also connects to an older moment in Jerusalem’s history. When King David captured the city, the Jebusites mocked him, saying that even the blind and the lame could stop him. The old saying then became “the blind and the lame shall not enter the house.” According to Christian tradition centuries later, Jesus healed the lame man at Bethesda and restored sight to the blind man at the Pool of Siloam (see John 9), effectively reversing the exclusion. Instead of rejection, the blind and the lame were healed and welcomed. It stands as a symbol of mercy and inclusion.

Practical Details:

Opening hours: Monday through Saturday from 8:00 to 12:00 and then 14:00 to 16:00. The site is closed on Sunday.

Admission: 12 NIS for adults, 10 NIS for students.

Site 2

Monastery of the Flagellation

The Monastery of the Flagellation, located at the beginning of the Via Dolorosa, includes two Franciscan chapels: the Chapel of the Flagellation, which commemorates the scourging of Jesus, and the Chapel of the Condemnation, recalling the moment when He was sentenced by Pontius Pilate. This is the traditional starting point for most Catholic pilgrimage groups walking the Way of the Cross, with Station Number 2 located just a short distance along the route.

According to Christian tradition, the area where the monastery stands is associated with the Praetorium, where Jesus was condemned by Pontius Pilate. Within the monastery grounds are large paving stones identified with the Lithostrotos (Greek for “stone pavement”) and linked to John 19:13, which refers to the judgment seat at a place called Gabbatha.

However, archaeological research suggests that these stones may not date to the time of Jesus, but rather to the period of Emperor Hadrian, and were likely laid after the destruction of the Antonia Fortress during the Jewish War (66–73 CE). Similar pavement stones can also be seen in the nearby Convent of the Sisters of Zion.

Across the street from the monastery stands the Omariyeh College, a functioning Islamic school. This site is often identified with the location of the Antonia Fortress, built by Herod the Great and named after his Roman patron, Mark Antony. The fortress served as a Roman military barracks overlooking the Temple Mount and is traditionally considered the location of the First Station of the Cross—though entry to the building is not always permitted. The Jewish historian Josephus describes the Antonia in detail, noting its strategic position and role in overseeing the Temple complex (Jewish War, Book 5).

Practical Details:

Opening hours: Usually open daily from 8:00 AM to 12:00 PM and 2:00 PM to 5:00 PM (hours may vary; check locally)

Admission: Free entry

Site 3

Convent of the Sisters of Zion

The Convent of the Sisters of Zion is a 19th-century Roman Catholic monastery built above significant archaeological remains along the Via Dolorosa. The site preserves part of a Roman pavement, traditionally identified as the Lithostrotos, and a section of a second-century Roman arch, once thought to be part of the Ecce Homo Arch. According to Christian tradition, this area is associated with the Praetorium, where Jesus was condemned by Pontius Pilate, as mentioned in John 19:13, at a place called Gabbatha.

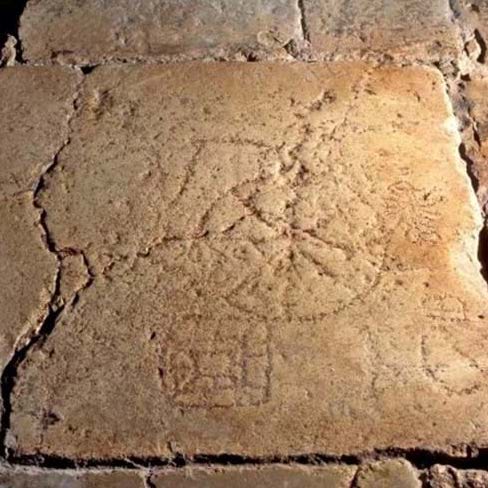

One of the most striking features of the site is a game etched into the stone pavement, believed to be the “King’s Game”—a Roman soldiers’ game in which a prisoner was mocked as a “king” before execution. Soldiers would crown, robe, and strike the victim—usually a condemned prisoner—mirroring the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ mockery before His crucifixion (Mark 15:17–19).

In addition to the pavement, the site includes deep water cisterns, likely used during the Roman and Second Temple periods, offering further insight into the complex infrastructure and layered history of the area.

The Lithostrotos pavement also extends beneath the nearby Monastery of the Flagellation, reinforcing the traditional connection between the two sites. However, archaeological research dates the visible stones to the time of Emperor Hadrian, after the destruction of Jerusalem in the 1st century CE.

The convent includes a quiet chapel and a small museum, offering visitors a space for reflection, faith, and historical discovery.

Practical Details:

Opening hours: Monday–Saturday, 9:00 AM–12:00 PM & 2:00 PM–5:00 PM

Admission: Small fee for groups or guided visits

Site 4

Via Dolorosa Station 7

This small chapel, maintained by the Franciscans, marks the traditional spot where Jesus fell a second time on His way to Golgotha along the Via Dolorosa.

Within the chapel are visible remains of the Second Wall, built in the Hasmonean period and later reinforced by Herod the Great. According to Josephus, it formed Jerusalem’s northern boundary during the Second Temple period. These remains help confirm that the present location of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was outside the city walls of Jerusalem at the time of the events described in the Gospels — even though it lies within the walls of the Old City today.

Practical Details:

Opening hours:

Usually open daily from 8:00 AM to 12:00 PM and 2:00 PM to 5:00 PM

Admission: Free

Site 5

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, located in Jerusalem’s Christian Quarter, is one of the most important Christian sites in the world. According to tradition, it marks the places where Jesus was crucified, buried, and resurrected. The church was originally built in the 4th century CE by Emperor Constantine the Great, after his mother, Helena, identified the site and is said to have discovered the True Cross.

Over the centuries, the church has been damaged and rebuilt multiple times, with the Crusaders carrying out the last major reconstruction in the 12th century.

Today, it stands as a complex and sacred space, shared by several Christian denominations — including the Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, and Roman Catholic churches — each of which controls different parts of the building. This delicate arrangement, known as the Status Quo, has shaped the daily life and traditions inside the church for centuries.

Read About the Traditions

Most of the sites within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are based on Christian tradition and serve as symbolic representations of events described in the New Testament. Many of these traditions were first identified during the 4th century by Empress Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, who is credited with locating key places related to the Passion of Jesus and overseeing the construction of the original church. Some additional traditions and chapels were established later, as Christian devotion and liturgical needs evolved over the centuries.

Two sites stand out as especially significant:

Golgotha (Calvary) is widely regarded by scholars and archaeologists as the most likely location of the crucifixion, based on historical, topographical, and textual evidence. It was outside the city walls during the Second Temple period, near a main gate, and adjacent to a known quarry — all consistent with Gospel descriptions.

The Tomb of Jesus, located inside the Aedicule, was originally part of a rock-cut cave, consistent with Jewish burial practices of the time. While the exact identification cannot be confirmed, recent archaeological research supports the likelihood that this area was part of a Jewish cemetery from the 1st century CE, adding credibility to the traditional location.

Visitors should understand that the church blends historical memory, faith, and tradition, making it one of the most important pilgrimage destinations in Christianity — even if not every detail can be verified with certainty.

What to See & Do:

Golgotha (Calvary)

The place of the crucifixion is on Golgotha, the traditional site where Jesus was crucified. When you enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, go up the stairs to your right to reach this upper level, built directly above the Rock of Calvary.

There are two adjacent chapels, both situated above the exposed rock:

On the left, the Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion marks the 12th Station of the Cross, where Jesus died on the cross.

On the right, the Catholic (Franciscan) Chapel marks the 11th Station of the Cross, where Jesus was nailed to the cross.

Between the two chapels, near the top of the stairs, stands a statue of the Virgin Mary, marking the 13th Station of the Cross — the place where, according to tradition, Jesus was taken down from the cross by Joseph of Arimathea (Luke 23:53).

Beneath Golgotha, accessible from the main floor of the church, is the Chapel of Adam. According to Christian tradition, this is where the skull of Adam, the first man, was buried. A crack in the rock, visible through a glass panel, symbolizes the belief that Christ’s blood ran down the cross and fell onto Adam’s grave — linking the crucifixion to the redemption of humanity.

The Tomb of Jesus (The Aedicule)

At the center of the Church stands the Aedicule, a small structure built over what is traditionally considered the tomb of Jesus. The current Aedicule was reconstructed in the early 19th century and underwent conservation work in 2016. According to tradition, this was the burial site provided by Joseph of Arimathea.

The tomb itself is inside a small chamber within the Aedicule. Visitors usually wait in line to enter the inner room, where they can see the stone slab marking the burial place. Entry is brief, and only a few people are allowed inside at a time.

Archaeological studies suggest that the tomb was originally part of a rock-cut cave, consistent with 1st-century Jewish burial customs. Excavations in the area also indicate that this was likely a Jewish cemetery during the Second Temple period.

The Stone of Anointing

Near the entrance, directly in front of you as you enter the church, lies the Stone of Anointing. This stone slab is traditionally believed to be the place where Jesus’ body was laid and prepared for burial after the crucifixion.

The current stone dates to the 19th century, but the location has been venerated since the Crusader period. The site is often surrounded by lamps and decorated by icons, and many pilgrims pause here to touch the stone or place objects on it for blessing.

The Tomb of Joseph of Arimathea

In a small side chapel near the Aedicule is a rock-cut tomb traditionally associated with Joseph of Arimathea, the man who, according to the Gospels, provided the burial place for Jesus. The exact identification is uncertain, but the site — which is included within the complex — is part of a Jewish cemetery from the Second Temple period, according to archaeological findings.

The Catholicon

This is the main domed area of the church and serves as the central worship space for the Greek Orthodox community.

Chapel of St. Helena and the Chapel of the Invention of the Cross

Located in the lower part of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, these connected chapels are dedicated to St. Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine. According to tradition, St. Helena traveled to Jerusalem in the 4th century and is credited with discovering the True Cross — the cross upon which Jesus was crucified.

The Chapel of St. Helena houses ancient cisterns believed to be the water source used by Helena during her stay in Jerusalem. The adjacent Chapel of the Invention of the Cross contains relics and displays related to the finding of the True Cross. The term “Invention” here means “discovery.”

These chapels are an important pilgrimage site, highlighting the connection between early Christian devotion and the physical locations tied to Jesus’ crucifixion and burial.