Golgotha (Calvary)

The place of the crucifixion is on Golgotha, the traditional site where Jesus was crucified. When you enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, go up the stairs to your right to reach this upper level, built directly above the Rock of Calvary.

There are two adjacent chapels, both situated above the exposed rock:

On the left, the Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion marks the 12th Station of the Cross, where Jesus died on the cross.

On the right, the Catholic (Franciscan) Chapel marks the 11th Station of the Cross, where Jesus was nailed to the cross.

Between the two chapels, near the top of the stairs, stands a statue of the Virgin Mary, marking the 13th Station of the Cross — the place where, according to tradition, Jesus was taken down from the cross by Joseph of Arimathea (Luke 23:53).

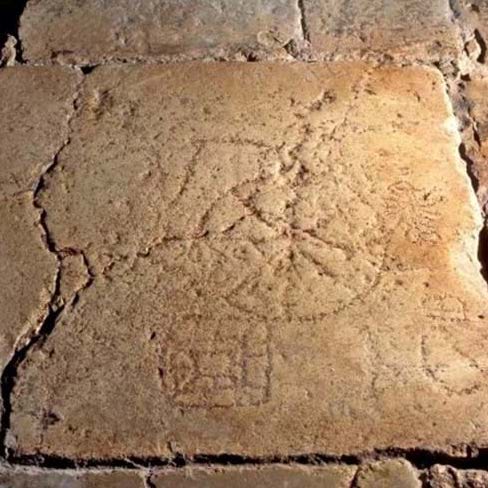

Beneath Golgotha, accessible from the main floor of the church, is the Chapel of Adam. According to Christian tradition, this is where the skull of Adam, the first man, was buried. A crack in the rock, visible through a glass panel, symbolizes the belief that Christ’s blood ran down the cross and fell onto Adam’s grave — linking the crucifixion to the redemption of humanity.

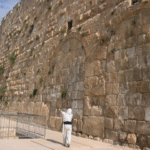

The Tomb of Jesus (The Aedicule)

At the center of the Church stands the Aedicule, a small structure built over what is traditionally considered the tomb of Jesus. The current Aedicule was reconstructed in the early 19th century and underwent conservation work in 2016. According to tradition, this was the burial site provided by Joseph of Arimathea.

The tomb itself is inside a small chamber within the Aedicule. Visitors usually wait in line to enter the inner room, where they can see the stone slab marking the burial place. Entry is brief, and only a few people are allowed inside at a time.

Archaeological studies suggest that the tomb was originally part of a rock-cut cave, consistent with 1st-century Jewish burial customs. Excavations in the area also indicate that this was likely a Jewish cemetery during the Second Temple period.

The Stone of Anointing

Near the entrance, directly in front of you as you enter the church, lies the Stone of Anointing. This stone slab is traditionally believed to be the place where Jesus’ body was laid and prepared for burial after the crucifixion.

The current stone dates to the 19th century, but the location has been venerated since the Crusader period. The site is often surrounded by lamps and decorated by icons, and many pilgrims pause here to touch the stone or place objects on it for blessing.

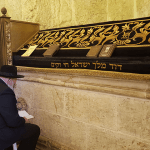

The Tomb of Joseph of Arimathea

In a small side chapel near the Aedicule is a rock-cut tomb traditionally associated with Joseph of Arimathea, the man who, according to the Gospels, provided the burial place for Jesus. The exact identification is uncertain, but the site — which is included within the complex — is part of a Jewish cemetery from the Second Temple period, according to archaeological findings.

The Catholicon

This is the main domed area of the church and serves as the central worship space for the Greek Orthodox community.

Chapel of St. Helena and the Chapel of the Invention of the Cross

Located in the lower part of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, these connected chapels are dedicated to St. Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine. According to tradition, St. Helena traveled to Jerusalem in the 4th century and is credited with discovering the True Cross — the cross upon which Jesus was crucified.

The Chapel of St. Helena houses ancient cisterns believed to be the water source used by Helena during her stay in Jerusalem. The adjacent Chapel of the Invention of the Cross contains relics and displays related to the finding of the True Cross. The term “Invention” here means “discovery.”

These chapels are an important pilgrimage site, highlighting the connection between early Christian devotion and the physical locations tied to Jesus’ crucifixion and burial.